I’ve already

written about how one of my most exciting moments at Research!America was visiting the National Institutes of Health (

NIH) campus for the first time. And in my second visit earlier this week, the excitement hadn’t worn off. It’s likely because, this time, I

and a few other Research!America staff got to see first-hand many of the things at the heart of the NIH: its history of discovery, its state-of-the-art clinical research hospital, and its talented researchers.

The day started with a walk led by our tour guide, Tara Mowery, who told us about the NIH’s

origins as a “hygienic laboratory” located on Staten Island back in the late 1800s. Eventually the National Institute (no “s”) of Health moved to DC and found a home in nearby Bethesda. One of many sights on our tour was building 1 – current location of Director Francis Collins’ office, and the first of nearly 70 buildings on the NIH

campus. Soon after, we entered building 10, the NIH’s hospital (pictured above), where we saw how researchers are literally taking their work from bench (a few hundred yards over) to bedside. John Burklow, director of the Office of Communications, followed up our tour with a presentation on the NIH’s organizational structure. There are

27 institutes and centers, but as Burklow emphasized, they’re all part of one NIH that is putting out news-worthy findings each and every day. Part of Burklow’s job, he added, is to ensure that the public understands the NIH’s expansive reach, especially with 85% of NIH research being done externally, at universities and other institutions across the country and around the world.

We then visited Dr. Marcus Chen, a staff clinician for the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (

NHLBI). Dr. Chen’s work is the kind of news-worthy research that Burklow had just described, as the

Laboratory of Cardiac Energetics is studying methods for decreased radiation in computerized tomography (CT) scans of the heart. There have been quite a few major

news stories recently about growing public concern over radiation and the increased use of high-radiation diagnostic tests, especially among children. By modifying certain parameters and using computer algorithms to improve imagery, Chen and his fellow researchers have been able to dramatically reduce radiation exposure. Pending further tests and development, this research could become the basis for safer, more patient-friendly CT scanning techniques at a hospital near you.

To wrap up our tour, Dr. Chen agreed to show us one of the CT scanners being used by his staff. It took a while, however, because machine after machine was being used for a patient. Eventually, we did get to see a scanner up close, but the wait was an excellent reminder of the NIH’s value. The clinical work done at its hospital not only serves and likely benefits patients today, but with continued discovery and development, the NIH also benefits the patients of tomorrow.

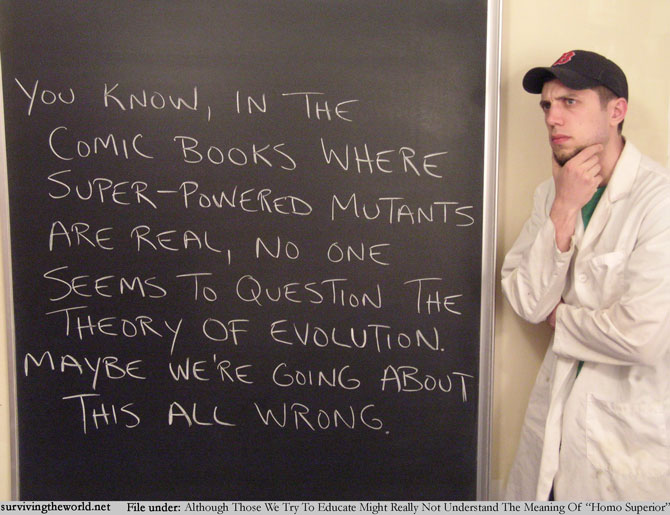

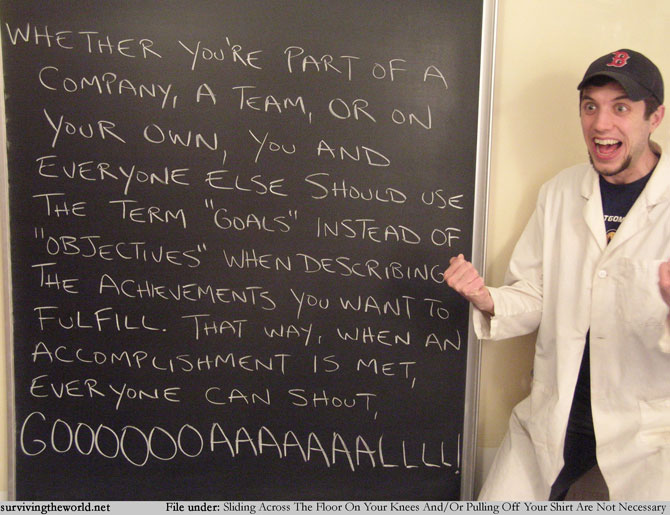

Comic credit: Surviving the World

Comic credit: Surviving the World